Excerpt from Chapter 10—preparing to go overseas

Hurricane Milton reminded me of something I thought I might do, which is follow my father and his unit through their actual combat experience because I have the morning reports for his platoon. They start with November 1, but his unit set sail earlier—right into a hurricane in early October.

A bit of background…Dad’s unit was the 325th Combat Engineers. He was a First Lieutenant in charge of Company C, part of the 399th Regimental Combat Team in the 100th Infantry Division.

Dad had been in training for three years. His unit, the 100th Infantry Division had been raided for replacements after casualties mounted in North Africa and Italy. He’d assumed that that’s what they were, a training unit, so he and my mother had gotten married and had one blissful summer together. Suddenly it was clear that something was afoot. As one GI wrote home:

No one has the faintest idea as to where we’re going and that’s keeping us in suspense. It’s not going to be so bad since we’re all going over together. We have a swell bunch of fellows and some good non-commissioned officers….They have cancelled all passes and furloughs. They may eventually give us one and then again they may not. That’s the army!

Mom went back to rural upstate New York to teach school because Dad insisted everything look normal, even though it was perfectly obvious the unit was on the move.

He didn’t have much time to write. Preparations were hectic. First there was a mass inspection of everyone and everything to verify the division’s combat readiness. The inspection made even enlisted men aware that “the glacier of our Division’s long immobility” was melting. The commander of ground forces had to determine whether the division was ready. General McNair, who had been the commander of ground forces and had been impressed by the 100th Division, had been killed by friendly fire in Normandy. The new commander of ground forces was a general who was a famous stickler for petty spit and polish. He was not impressed. He failed the division. When General Burress, head of the 100th Infantry Division, got the news, he appealed to his friend, Chief of Staff George Marshall, who over-rode the findings. The commander of ground forces supposedly told Burress, “if the war is over when this outfit goes overseas then, God bless you, however, if the war is still on, may God help you.”

The next order of business was coating all vehicles, equipment, and weapons, inside and out, with cosmoline. I've encountered many extremely unflattering references to cosmoline in memoirs. It’s a brown, waxy form of petroleum jelly that the Army used to prevent rust from sea water. When fresh, it can be smeared around with a rag into every nook and cranny, but as soon as it’s exposed to air, it hardens. And the more it hardens, the harder it is to get off anything, let alone all the moving parts of complicated machinery.

In addition, everyone had to mark the upper inside of all their pants with their initials and the last four numbers of their serial numbers, they had to watch the propaganda films created by Frank Capra called “Why We Fight,” and they had to sort their belongings because they were allowed only seven pounds of personal effects. By September 13, they were sending their trunks home by railroad express with everything else they owned. It wasn’t all grim. On September 12, Mickey Rooney put on a show at Fort Bragg. This might be why Dad always had a soft spot for Mickey Rooney.

While it was perfectly obvious that something was up, the Army insisted on secrecy. One of the riflemen wrote home on September 23 that “I have to be careful now what I say in my letters home. They are spot checking all outgoing mail and this might be censored. A Staff Sergeant was court marshaled today for giving away military information. He told his wife when and where we are going.” I'm not sure what that sergeant had to write other than scuttlebutt because not even officers knew where they were going—except to Camp Kilmer, the last stop before sailing from the port of New York City. The one comfort they had was that they were going together, unlike the men who went through the replacement depots. The men all dreaded getting separated from their unit in the sea of Army red tape. On September 27, 1944, Mom got the preprinted postcard that said Dad’s address was now APO, NY, NY.

As the date neared, everyone was confined to base. Then, Dad’s friend, Carl Blanton’s grandmother died. He remembered how grateful he was that the lieutenant of his platoon, Bell, gave him a pass to go to the funeral. Bell trusted Carl’s word that he’d be back in time for them to ship out. Sixty years later, Carl told us how much that trust meant to him. To which his friend Wallis replied, “Yeah, he trusted you because he knew you ate better in the Army and you’d be back.”

On September 28, the 15,000 men of the 100th Infantry Division boarded the train for the two-day trip to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, which served two functions. It prepared the men for life on shipboard, and it winnowed out men unfit for combat. There was a big chart on the wall with the names of every man in each of the units with squares to be checked off next to every name. There were squares for vaccinations—so many vaccinations that they were lame and black and blue. There were squares for filling out wills and life insurance and squares for marksmanship tests, physical tests, and psychological tests. There was a last-minute medical exam with whole companies stripped down to their shoes literally running from doctor to doctor to spread their buttocks and stick out their tongues. Rumor had it the 100th Division lost only two—one guy with hemorrhoids and another with a hole in the back of his head no one had noticed before. If a soldier failed a test, he vanished from the unit and a stranger was dumped into his place. Some units took the opportunity to shed their misfits by sending them to New York City on a pass the day the unit sailed.

A memorable experience in Camp Kilmer was the abandon-ship drills—the men had to clamber down a cargo net and into a lifeboat rocking in a tub of water. They also had to test their gas masks by going into gas chambers. They heard lectures on the Geneva Convention if they were captured and, somewhat oddly, they learned about the point system that determined the order in which they got shipped home after the war. Maybe the Army wanted to encourage them to act above the call of duty because men with the most medals got out first.

Dad, who was the lieutenant of his platoon and second officer of Company C, kept the lecture on secrecy that he had to give at Kilmer. It explains in part why so many letters that the men wrote home are more than vague. They often completely misrepresent their situation. As the lecture said:

When writing home: Think! Where does the enemy get his information—information that can put you, and has put your comrades, adrift on an open sea; information that has lost battles and can lose more, unless you personally vigilantly perform your duty in safeguarding military information.

There were ten prohibited subjects, but basically, they couldn’t describe anything—not convoys, not locations, not destinations, not transportation, not casualties, not plans, not equipment, not numbers of men in their units, not the enemy, and do not try to invent a code to get around the censor. Since the men themselves didn’t want the homefolks to worry, letters from overseas need to be taken with a very large grain of salt.

Camp Kilmer provided large banks of telephones for men to make their last calls home, but after all the lectures, the calls themselves, which could be overheard, were awkward. The habit of leaving things unsaid had begun.

In the midst of the inspections, tests, injections, and lectures, each man was offered a twelve-hour pass to Manhattan. A young soldier wrote to his folks about his day. He tried to see some people he knew, checked out St. Patrick’s Cathedral, watched a ping pong demonstration, enjoyed the Stork Club, saw a program at Radio City Music Hall, and ate at a Swedish restaurant. Dad’s friend T.C. sent home a photo of himself in a New York nightclub, drink and cigar in hand, with his buddy Norval Jones. He labeled it “What a night.” T.C. was from rural Georgia, so New York City was an experience to remember even 55 years later when he was talking to me.

Dad sent Mom a photo from the Stork Club with her good friend “Ugly” Williams and Lr. Willie Williams. It had to hit like a knife in the heart because Dad in his urge to save lives through secrecy had sent her home. Apparently, Willie Williams didn’t have the same qualms.

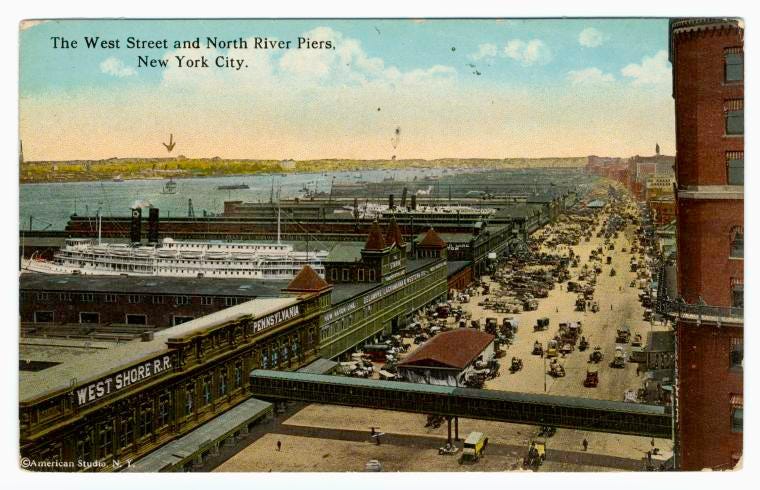

When all the squares were checked off, the units were ready to sail. They were given an escort from Kilmer to their ships by armed military police. There would be no second thoughts. The lecture on secrecy had pointed out that desertion meant death by firing squad. The men had to carry a 70-pound field pack with a horseshoe bedroll, their rifle, an overcoat, cartridge belt, and steel helmet to the train. When they got off the train at the ferry, they were given their 100-pound duffle bags. Most of the men were carrying more than their own body weight as they walked along the docks, looking for the right ship according to the number scrawled in chalk on their helmets. They shuffled up the gangplanks to the sound of dance music from the band stationed at the 43rd Street pier.

Good job. My father-in-law was in Love Company of the 399th and talked extensively of his experience toward the end of his life. He was seriously wounded by a mortar shell in November 1944 near Raon l’Etape in the Vosges Mountains…treated at Epinal and St. Die, put on a hospital train to Paris and then to the Royal Victoria hospital in Netley, near Southampton.

Looking forward to more of your narrative.