To recap: the 100th Division spent the winter of 1945 just outside Bitche on the German border, in constant contact with the German front line, waiting for other divisions to eliminate the Bulge and the Colmar Pocket.

With warmer weather in February, came clearer skies and the 100th Division became very aware of the flights of bombers headed for Germany overhead, with greater numbers all the time, building to the infamous thousand-bomber raids. As one of the GIs noted, they cheered them on—especially if they could keep the Luftwaffe off their backs, but they were also very aware that those guys could fly back home to England, go to the pub, get their daily showers and hot meals, and have a girlfriend to keep up their morale. They probably weren’t aware of the horrific casualties that privilege came with.

The 325th Engineers, Company C, had its own encounter with the air force one day to break up the monotony—a story both TC and Dad told me. They could hear that there was a plane coming down. Dad, Bagley, and Bell (with TC) saw a parachute emerge and realized it was dropping in their sector so they jumped in their jeeps and headed that way. When they got there, the guy in the parachute was caught up in a tree. As TC said, “the damn fool was yelling all the time and wiggling.” They shouted up to him that they’d get him down and he should stay still, but he wouldn’t listen, so he fell to the ground and broke his leg. When they got to him, he seemed okay except for the leg. He just kept going on about how his wife would take the news that he’d been shot down. Bell and TC took off to where they thought the plane had gone down so they could strip any parts off it that they might find useful before anyone else got to it. Bagley and Dad stayed with the flyboy who was wearing a clean pressed uniform. He finally asked them where he was. They told him he was on the front lines on the border of Germany, and he went rigid. As far as Dad could tell, he had seemed physically ok, apart from the broken leg, until he got the news he was on the front. Dad seemed to think it was a kind of hysterical paralysis. They got him to the medics and he was safely conveyed to the rear, leaving them on the front, leaving them a bit disgusted and baffled.

At least the weather was good, even if he had no sense that his war could be over soon. Dad wrote to Mom at the end of February—

Letters few and far between—very sorry. All the snow you are having makes me feel for the home folks. We have had some clear sunny days now for quite a while, ground is beginning to dry up. Found some pussy willow today, a lot of new birds around too.

Took one of my reconnaissance trips the other day it was so nice, supposedly looking for road materials, nearest excuse I could find. It is really nice country, scenery is beautiful. Bagley and I took a nice long hike this morning to look over some of our projects. I had a dream last nite, stopped by to say hello on my way to the Pacific. Pleasant, what?

Good nite, Love Gordon

By the end of February, the sun was out and warm and the men came out of their layers. Dad’s platoon seems to have found a source of cameras.

Orders from the rear were issued to police the area—meaning to tidy up the mess of cans and ammunition shells and debris from winter—but, as the 399th history points out, no one from the rear echelon came to check. The engineers were doing what they could to make the roads passable with the handmade culverts and corduroy roads of felled logs. On March 4, my Dad, Lt. Gordon Morse, turned 29.

By early March, there were signs a thaw was happening on the front and not just the weather.

The news kept coming in that the Russians had the Germans in retreat in the East. The guys said they were happy to wait at Bitche for the Russians to get there, but by early March, there were signs that a change was coming even for them. For one thing, the Germans they’d faced all winter seemed to be losing hope. They were starting to deal with deserters, enough that the U.S. Army was dropping pamphlets and sending radio messages, promising them warm housing and plenty of good food if they surrendered. Patrols reported fewer and fewer contacts with Germans troops.

There was another sign that the front was about to change—fresh troops. As TC recalled:

I know one time another division was coming through our division in Alsace Lorraine and we’d been in there several months. They were a new outfit, all nice clothes. We had a guy who had size 14 shoes, but no new ones. He looked like a Civil War veteran. He had his feet all wrapped up in a blanket. And these new recruits were looking at him. He had white hair and these bad shoes and beat up clothes and they were staring at him. The shoes couldn’t catch up with him on the front.

The 100th Division through their time in combat had 86.7% turnover (out of 15,000 men, there were 12,215 casualties--killed, wounded, and nonbattle injuries and diseases). Other divisions had it worse. The 3rd Division had 201.6% turnover through the war. So a lot of men got filtered through the Replacement Depot system.

In early March, replacements started showing up all through the Division, though a lot of the old timers just rolled their eyes at the “inexperienced eight balls”1 In the artillery, a brand new executive officer showed up and ordered all the trucks massed to be ready to go. An old timer warned him that that was a bad idea but he refused to listen. Sure enough, all the trucks got shelled.2

T.C. remembered wondering what the hell he was doing in the mess line with strangers. Where other countries pulled understrength units off the line to reconstitute them and help them form the essential unit cohesion, the U.S. just inserted individuals into the unit with no training and no cohesion.

The fate of a replacement was not good. They sat in a replacement depot, sometimes for months, with no unit, no buddies. Then they were thrown on a truck and dumped off into a unit where someone had died or been wounded or cracked, so there was already bad karma. They made stupid errors and endangered others around them, being green. And many had just had boot camp. They weren’t trained in the infantry—which is a specialized expertise. Some weren’t just fresh from the States. Many were from rear echelon units who had no idea how to fire, let alone maintain, their rifles. The old timers avoided them because they made dangerous mistakes. Too many were killed or wounded before their paperwork arrived.

Another route through the repple depple was through a medical aid station. The first get to a man wounded or ill was the platoon or company medic with his limited training. Bob Heller was a Company C medic. He told me how he got the job. An officer had told him, “drop your rifle, Heller, you’re the medic.” He was given a book on horse anatomy and followed some of the other medics around. He had morphine, aspirin, and bandages as his arsenal.

The medic would load men on a jeep and bounce along what roads there were to a temporary aid station. If the wound or condition was bad enough, they then were put on a litter and put in a truck with tiers of litters to get to a field hospital with an operating room for emergency treatment. Then they were sent further to the rear to a hospital with beds, warm food, clean clothes, and quiet. If they couldn’t heal in the hospital, they were shipped ever further west, eventually to a hospital ship bound for New York. As primitive as it could seem, if a man made it to the battalion aid station, only 3.5% died of their wounds and 3/4ths of the men returned to some kind of duty. The question in the men’s minds were, what kind of duty? If it was back to the front, they were desperate to get back to their old unit, where men they knew would have their backs.

If they stayed away too long, even returning to the same unit might not help. One of the 399th recalled getting out of hospital after two months. He was very happy when the repple depple sent him to his old company, only to find that his old buddies were almost all gone. With his clean clothes, he was treated like a raw replacement.

TC told me his story of getting into the medical system. One time, he was desperately tired, so Lt. Bell was driving the jeep while he slept. Suddenly Bell hit something or something hit them and they were flung from the jeep. TC literally didn’t know what hit him because he was knocked unconscious. The first time he woke up, he was all the way back to the hospital far to the rear. When he realized where he was, his only thought was how to get back before anyone thought to take him to a repple depple for reassignment. So, he got his dinner, waited until night, grabbed his clean clothes, and slipped out of the hospital. He got to the road and started thumbing rides with supply trucks. The first one had no idea where the 325th Engineers were, but he knew where the 100th Division was. From the 100th Division sector, TC found a truck that knew where the 399th Regiment was. That got him in range of someone who knew where Company C of the 325th Engineers was and that got him home to his 1st platoon. In other words, TC went AWOL in order to get back to his unit.

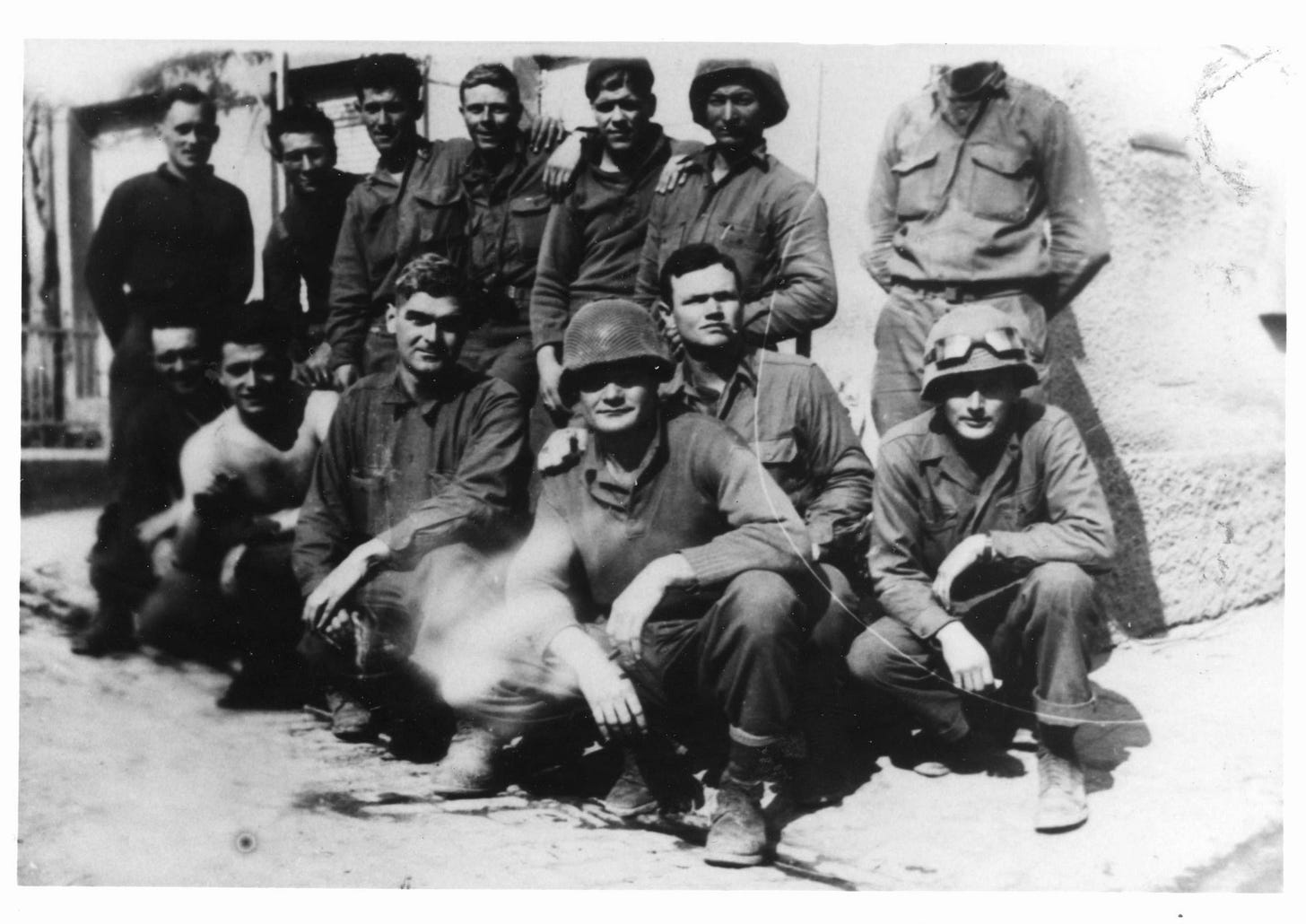

Here’s TC’s platoon, his band of brothers. He often repeated to me that he loved them all. The guy in front is Omer Fountain, good friend and another Georgia boy. TC is the one with his hand on Omer’s shoulder. To his left, is Lt. Bell. Carl Blanton is the fourth from the left (or right) with his hand on the shoulder of the guy next to him.

(Angier p. 64)

(Fishpaw)

Thanks Patricia, I enjoyed the story very much