In June 1944, the 100th Division was stuck in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. They had spent 14 months and a great deal of time, effort, and money creating an optimal level of unit cohesion and efficiency—the kind that is essential for the best performance in combat. When they arrived in Fort Bragg in January 1944 after months fighting mock battles across Tennessee, the Army tore the division apart. Rather than send the division as a unit overseas, they grabbed thousands, dumped them into replacement depots overseas, and plopped them randomly into units that had been decimated in the fighting in North Africa and Italy. Coincidentally, many of them ended up in the 3rd, 36th, and 45th Divisions, all of whom would end up next to the 100th Division in France. At least the men sucked out of the 100th Division were thoroughly trained, unlike some of the poor guys dumped into the front later in France, where stories were told of men from the replacement depot turning to the man next to them and asking how to reload their rifles. The Army violated in the most fundamental way the psychology of how men handle combat the most effectively--they fight for their buddies. The “band of brothers” is not just a cliche.

The skeleton of the 100th Division left behind in Fort Bragg suddenly looked like a training division, destined to process others but never to go overseas. The men who were left behind were thoroughly disgusted. Their friends were gone, the units hollowed out, and the only prospect after all that training was more training. There was nothing more, after the experience in Tennessee, to be learned. It wasn’t so much that they wanted to see combat, but they wanted the experience of being yanked out of their civilian lives to count for something more than years of "chickenshit." While the 325th Combat Engineers had not been torn apart as badly as the infantry units, as part of the division, they were still stuck, repeating what they had already done. As it turns out, being stuck Stateside was an experience far more common than combat. There was an old joke in the 1960s--what did you do in the war, Daddy. And the answer for millions of men was, not much. In early 1944, it looked as though that was the fate of the 100th Division—garrison duty in the hot bleak fort.

In May, one infantry captain told his company of the 399th that they had definitely been designated a training division for replacements.1 He had some reason to say that. Up until August 1944, 14,636 enlisted men and 1,460 officers were trained within the division and then shipped out as individuals to replacement depots. In other words, a full extra division’s worth of men passed through.2

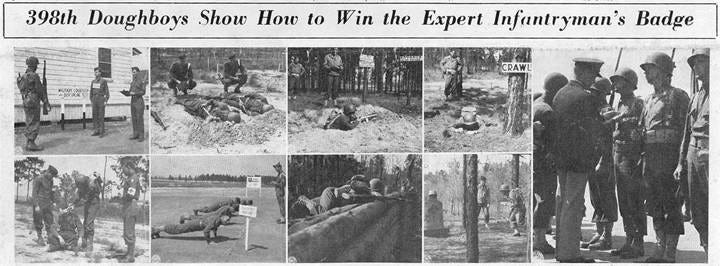

Morale for the vast majority of men in infantry was bad especially in the large number stuck Stateside, so the Army created the Expert Infantryman’s Badge to reward infantry training. Better than the badge was the boost to morale that a man got from the extra $5 in his monthly paycheck. The very first EIB was given to a man in the 399th Infantry Regiment. The New York Times lauded the recipient, Tech Sergeant Walter L. Bull, who had done well on the 30 tasks of the EIB test—things like accuracy in the firing range, endurance on marches over specified courses, skill at map reading. The men of the 399th who lined up to witness the first badge regarded the affair with a certain amount of cynicism. Everyone was fairly sure one reason Bull was first was because he had gotten a medal not long before for rescuing civilians from a burning train wreck outside Baltimore. The rumor around the regiment was that he’d escaped the train wreck without rescuing anyone, then remembered that there was a large whiskey inventory in the box car, so broke back in and accidentally found some civilians on his way to the booze.3

After the dog and pony show of the Expert Infantryman’s Badge, there were more signs that the 100th was being used as a show division. In March, the 397th Infantry Regiment combat team put on an entirely scripted “massed attack on a fortified position” with coordinated artillery and infantry for the undersecretary of war and assorted Washington dignitaries. A few weeks later, the 397th put the show on again, this time for Secretary of War Stimson and a higher level of war brass. They liked the show so much, that they ordered a third performance of the same show, this time for 40 members of the press, radio, magazines, and newsreels. The New York Times was one of the newspapers on the scene to watch the 397th combat team attack a fictitious position, using 110 tons of live ammunition. The event concluded with yet another snappy review of marching troops. The Times reporter, perhaps a bit suspicious, questioned General Burress about whether all these war games were necessary. Burress replied “We’re likely to be thrown right in against the best European troops. We’re not going into an old lady’s home, you know. We’re going in to fight Germans.” The men weren’t reassured. They knew the Germans didn’t follow a script.

The division’s own newspaper reported on the performance. Also in the issue was a column of gripes from the men, a page of sports news about the division’s teams, and various gratuitous pictures of pretty girls. The general tone was that they were all just killing time.

It filled them with complicated emotions when news came of D-Day. One of the men recalled what D-Day was like at Fort Bragg:

Before daylight on 6 June 1944, we were awakened by distant sirens, whistles, and church bells. Radios were turned on and we heard General Eisenhower saying that the Allies had put men ashore in Normandy a few hours earlier and that the invasion was so far a success. General Burress and his staff participated in a D-Day prayer session at the Division Chapel….This reopened the old discussion of when (if ever) our Division would go overseas. While nobody I knew was shedding tears over the fact that we had not been present for the ‘grand opening’ of the European ‘theater” on 6 June on those fire-swept Normandy beaches, we were nevertheless an infantry division and an infantry division was trained to fight.4

D-Day did have an effect on the 100th Division. On June 12 ,1944, as reported in the New York Times, 1,200 men from the Century Division, mostly men with Expert Infantry Badges, were shipped up to march in a parade up Fifth Avenue as part of a big War Bond drive and as part of Infantry Day, yet another attempt to puff up the importance of the dogface soldier on the ground. The Division’s 80 piece band and 60 member drum and bugle corps marched too. The ticker tape parade drew 700,000 spectators. As the New York Times put it “a battalion of crack infantrymen from Fort Bragg paraded from the Battery to City Hall.” An honor guard stayed for awhile to guard Radio City Music Hall. Heroes from the fight at Anzio were on hand to receive medals. One of the men from the 100th recalled the march. They gathered on 81st Street in their khakis, steel helmets, light packs, and rifles. The spectators were crying, though of course, not for them. He had to focus on the effort to maintain a straight line that was 50 men wide, let alone turn a corner in formation.5 As part of the launch of the $4 billion campaign, there was a display of items in Central Park, with the price tag marked. The clothing for an infantryman cost $70, a Garand rifle cost $180, a jeep cost $800, an antitank gun cost $6,375, and a howitzer cost $30,000.6

Dad had been drafted in April 1941 into the 28th Infantry Regiment, the Wampus Cats. He’d spent over a year rising through the enlisted ranks to sergeant. Many of the men had come from his area of upstate New York. He didn’t know where they we were on D-Day but he’d known that his old unit was overseas.

As it turned out, Company L of the 28th Infantry Regiment, the Wampus Cats, left Belfast and came ashore at Utah Beach on D-Day + 28, July 1. They entered combat in the hedgerows of Normandy at La Hays du Puits on July 8. The bad leadership Dad had feared and despised came true. The officers insisted they move forward with unprotected flanks. The casualties in the first day of combat were devastating. When I was at the cemetery at Normandy, it took no time before I found men from the Wampus Cats.

I don’t know when Dad heard that his old unit was getting badly shot up, but I do know that in July, he got news that his good friend, Pee Wee Shutter, had been killed in Normandy. He knew because Mom sent him a notice in the local paper. Pee Wee had been a local boy:

Staff Sgt. William J. Shutter, son of Mr. and Mrs. George Shutter of Ravena, was killed in action July 19 in France, his parents have been informed. Known as “Pee Wee” Shutter, he fought in the bantamweight class of the Golden Gloves tournament in Albany before entering the service. He had been overseas more than a year. He was employed at the YMCA in Selkirk. He was killed two weeks after his cousin, Cpl. Robert Shutter, son of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Shutter of Ravena was reported killed in action in the Mediterranean theater.

As combat around the world intensified, the men of the 399th kept asking their officers whether they would be going overseas. It happened so many times that the colonel, a difficult man named Tychsen, got so disgusted, he said that anyone who wanted could volunteer to be replacements in the airborne since the 101st and 82d had taken heavy losses in the Normandy hedgerows. He thought the idea of heavy losses would deter them, but hundreds from the regiment applied for a transfer. General Burress ordered Colonel Tychsen to talk the men into staying, which he managed to do, enough anyway that he still had a regiment.

In June, the artillery and the engineers went to Myrtle Beach to practice a beach landing complete with howitzers, so they thought there might be a change in plan. In July, the division was temporarily issued camouflage utility uniforms and taught jungle warfare so the men thought they might be going to the Pacific. Later, the 399th had ranger training and the rumor flew that they were going to Norway. But the most persistent rumor was that they were only a show division.

The 100th Division seemed mired in Army “chickenshit.” On July 19, a battalion of the 399th put on a show for a group of Southern cotton growers, who then dressed up in fatigues and pretended to be military. Apparently, Southern cotton production was seriously slacking off, and the military wanted them to get some team spirit to boost production and stop manipulating prices. As Frank Gurley of the 399th said about the exercise, “wotta farce.”

(Knight p. 34)

(Story of the Century p. 34)

(Gurley, p. 34).

”(gurley p. 49)

(Hancock p. 57)

(New York Times, June 16, 1944, “City Pays Tribute to the Infantry”)