I’m a bit behind real time, since the jump off the line to head to Germany was March 15, 1945.

Dad had a trip to Paris just before they jumped off the line to. It wasn’t the thrill that sounds like. Dad and his friends I talked to had nothing good to say about Paris. When Mom and Dad did some traveling in retirement, Paris was never a destination.

An enlisted man in the 399th remembered what the trip to Paris was like for him. He got a hot shower (his third since arriving in France) and clean clothes in Nancy. He walked around but hated being back in Army hierarchies and resented the rear echelon personnel. The next morning, he got on a convoy of trucks where the enlisted men were packed like sardines. They drove slowly on the traffic jammed highway toward Paris. Dad on his trip got to drive his Mercedes command car, at least part of the way. Going to the rear meant he once more got the perks of an officer, not just the responsibilities.

Their first stop was to the Red Cross center of Paris1 From there they got a billet at one of the hotels. The rooms were private but there was no hot water and very little heat due to the intense coal shortage that winter. He ate at a “swank” restaurant with English-speaking waiters, while a small French band played American music.2 There were writing rooms, and theaters, and a PX where they could buy Coca Cola and souvenirs.3

When it was time to leave, they were back on the trucks for a long day before reaching Nancy where they changed trucks to get back to his company area. He spent the night with the cooks (“what a racket those guys had—they lived in houses most of the time way out of the danger of war”), then rode up with them to the front when they drove up the chow in a jeep.4 It was an entirely disorienting experience.

One of the ways I think the war changed Dad was the education in human nature during the war, and much of it was bad. He trusted the people he liked, but he had a profound cynicism about the motives of much of the world. Certainly, the two-day plunge into Paris did not lead one to think the best of humanity.

First of all, was the condition of Paris itself. Though it had not been shelled or bombed, it had suffered through shortages and experienced deportations and German “tourism.” The city was black with grime, and the fountains didn’t work. The people stomped down the streets in wooden shoes because there was no leather. The skirts were short for all the women because fabric was so limited.5 Unfortunately too many GIs thought the short skirts signaled availability and there were confrontations.

One of the problems was that the French civil authorities didn’t control their own city. Even TC noticed that. His leave happened later, I think after VE day. He went to a bar in Paris and got a beer. He took it to a far corner table. As he sat there, a brawl broke out between the 101st Airborne and the 82nd Airborne that turned into a donnybrook. As he sat and sipped his beer, watching the brawl, he heard whistles, the French gendarme came running in through the door, skidded to a stop when they saw who was brawling, and ran back out the door.

Worse than brawling GIs, however, was Lt. Gen. John C. H. Lee, commander of Services and Supply, sardonically referred to as the Blue Star Commandos, for the blue star on their uniforms. He was, as Stephen Ambrose concluded, “the biggest jerk of the ETO.”6 Eisenhower had ordered him to stay out of Paris, both to save gas and supplies for the troops but also not to burden the Parisians suffering from shortages, but he moved the S&S into Paris anyway. They took over all the hotels, the schools, and large buildings. By March 1945, there were 160,000 Service and Supply troops in Paris.7 One veteran pointed out that most of the men in Service and Supply experienced the war as a “period of undesired and uncomfortable foreign travel.”8

With the entire materiel for the ETO passing through their hands, Service and Supply was in the perfect position to make a profit in large and small ways in the only economy that was functioning, the black market. “Thousands of gallons of gasoline, tons of food and clothing, millions of cigarettes, were siphoned off each day. The gasoline pipeline running from the beaches to Chartres was tapped so many times only a trickle came out at the far end..”9 That happened in even petty ways. One of the engineers got a box from home with the contents missing and a note inside from the GI post office in Paris. The clerk was a former member of the squad who had gotten reassigned from the medical tent. The note said that he remembered what a good baker the dogface’s mother was, so he took the cake. The guys on the front were very bitter.

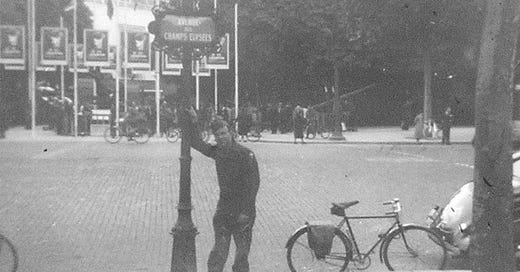

Because the French economy was in shambles, everyone did what they could to get what they could. There were registered bordellos but Paris was notorious for “free lancers.” From the moment they got off the transport, men with the green combat stripe on their sleeves were targeted as sources of profit. As one 100th Division GI recalled, he got off the transport and his arm was immediately grabbed while prices were shouted at him: “baby, zig zig 200 francs”10 As he said, “I was no goody goody, but this was depressing.”11 The most notorious location for the free lancers was the rue Pigalle, which the GIs called Pig Alley. Bob Heller even took a picture of the Metro stop, though he told me he was too naive to handle it all.

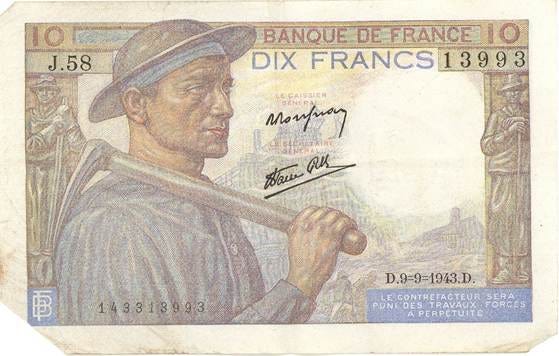

Francs weren’t worth much. Dad sent two franc notes home in a letter. As he said, combined, “The francs represent $2.20 so don’t throw away.”

Cigarettes were a better currency than the franc notes. A cigarette kept its value.

If GIs kept to official areas on their two days, they usually stayed out of serious trouble, but there were thousands of deserters in Paris living off serious crime, so there are some harrowing stories of the dangers of Paris.

Even a relatively good leave was wrenching. In the relative peace and quiet, their minds started to process what they had experienced. But then returning to the front, as even Dad reported, they found that the insulating dulled senses had gone. All the gut-wrenching fear came back as bad as the first day on the front.

Of course in the letters, they put a good face on it. Dad wrote to Mom that he’s mostly happy about finally getting cleaned up:

10 March 1945 "Somewhere"--"

Back from a four day furlough, can't get used to noises. All that I heard in Nancy was horns blowing. Had a very nice hotel room, would equal anything in the States. Like to feel those sheets. Universal went out in my car. It is in an Ord. depot between Nancy and Paris. Sounded like a German Minnie woofer going by when it went out. Wish you could see my new combat blouse, looks like Patton's. Certainly feels good to get dressed up in the pinks again and strut around. My German and French conflict on occasions, get to express myself in various tongues.

Four days after his return, the engineers were loading up lumber on trucks to have for improvised bridges on the path into Germany. A day after that, March 15, the 399th regimental combat team jumped off the line toward Bitche. As the morning reports noted,

Lt. Morse and 2 men went along with the attacking company to supply engineer assistance, removed friendly mine field and right after were pinned down by a heavy mortar barrage. Co F located extensive schu mine field and requested several gaps. At 11:30 Sgt Drewes and two men made the gaps and encountered heavy artillery fire.

(Knight p. 107)

(Knight p. 108)

(Knight p. 108)

(Knight p. 109)

(Gimlette p. 159)

(Ambrose p. 336)

(Ambrose p. 338)

(Fussell War p. 282).

(Ambrose p. 338)

(Gimlette p. 168)

(Gimlette p. 169)

Thanks again for a view of these events that I have not had. I should have known more by my age, but I'm still learning, and you are one of my guides into the past.