On November 11, the men of the 100th Division, newly arrived at the front, observed that it was Armistice Day. To them, it still meant the eleventh minute of the eleventh day of the eleventh month when the world stood still to remember the moment when men stopped killing each other in World War I. For them, it was also the day before Operation Dogface, the assault on the German Winter Line. The entire 7th Army jumped off on November 12.

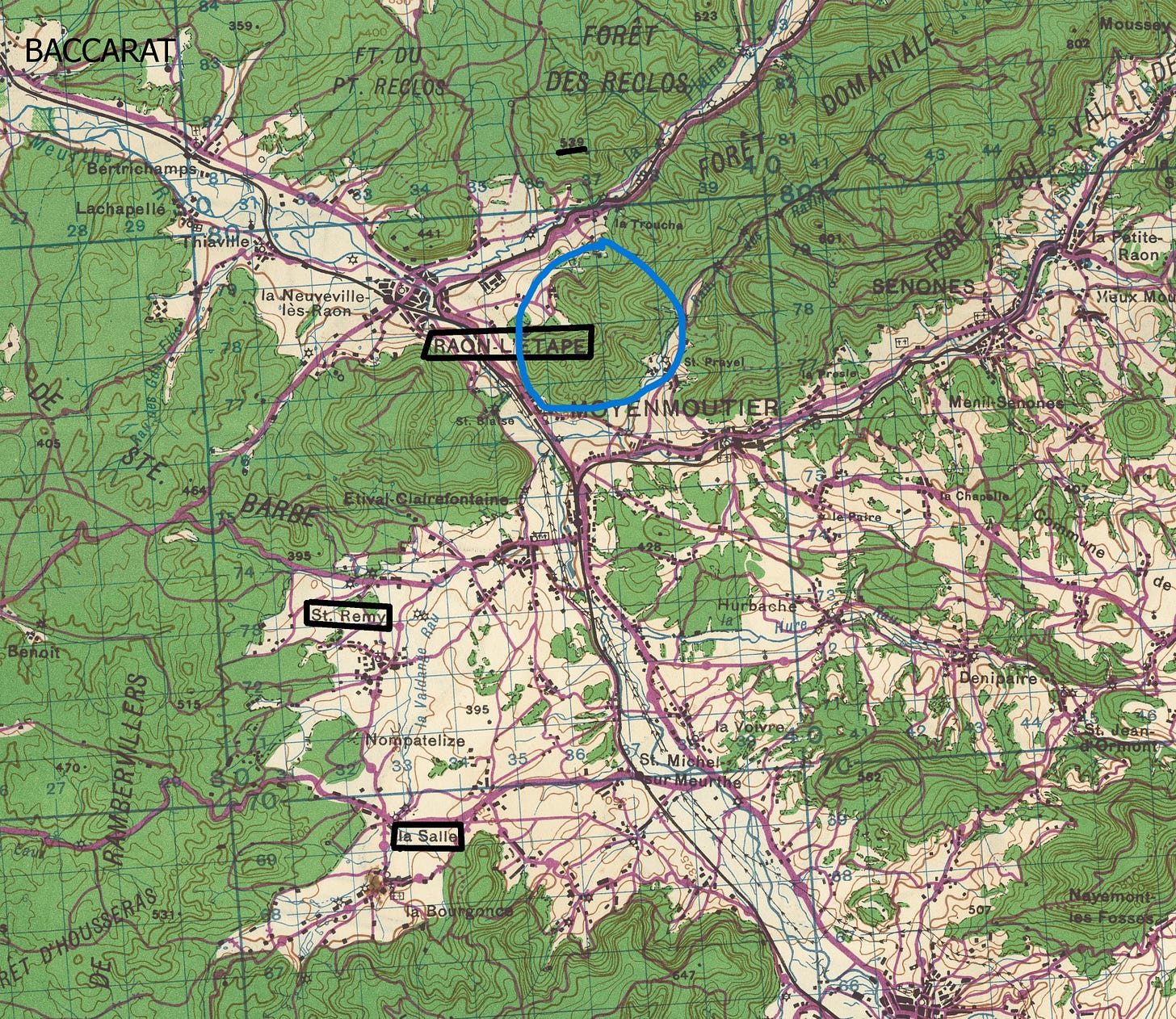

Operation Dogface was the name of the Seventh Army’s next assignment—to break through the heavily fortified Vosges Mountain passes to reach the Rhine Valley beyond them. One of the main routes through the mountains was the Pleine River, which met the Meurthe River in a town called Raon l’Etape. The mountains surrounding it were heavily forested, especially two to the southeast. The lower one was heavily fortified to protect the artillery there. The taller one behind it was fortified to protect the lower one. While these mountains are not that tall in the universe of mountains, they were straight up, heavily forested, heavily mined, and a network of bunkers and machine gun nests.

This was an assignment that had already failed twice. In late September, the British had dropped airborne special forces to make contact with possible French resistance in support of what they thought was the fast approach of Patton’s Third Army. What they didn’t know is that the Germans had moved in to construct the winter line. The project was a disaster. The young men of Alsace had been conscripted and sent to the Eastern Front, from which few returned. The Germans, when they realized the British had shown up, tracked them down and rounded up any Alsatians who might consider resistance, including the mayor and city officers of Raon l’Etape and executed them against the city hall. The Germans arrested 210 residents and sent them to concentration camps. Only 70 returned after the war. Then, at the end of October, the 45th Division tried a frontal assault across the Meurthe River into Raon l'Etape and failed.1

General Patch, commander of the Seventh Army, handed the assignment to the 100th Division. One regiment had been at the front a bit over a week and the other two had just arrived. The Army’s historians forty years later thought the assignment was “extremely ambitious for the new division.”2

General Burress decided to use actual tactics instead of another frontal assault across the Meurthe. In simplified terms in what was a large battle, he lined up one regiment, the 397th, across the Meurthe for another assault, which would hold the Germans’ attention since they had gotten used to the Americans doing straight assaults, one after the other. The other two regiments would cross the Meurthe River at Baccarat, which was already in Allied hands, and fight their way down the other side of the river to the Pleine. The 398th would fight in the valley. The 399th would cross the Pleine, go up the far side, the steepest but somewhat less fortified side, of the two guardian mountains and take out the artillery and defenders.

Through a fluke, I have the exact contour map for this region. Evidently, the Army recycled their battle maps with all the contour lines and buildings marked as paper to print inspirational posters on during the occupation of Germany. It must have been an eerie moment when my father happened to notice that the back of one of the inspirational posters was the very ground he’d fought over all those months before. He sent it home with the admonition, “don’t throw this out.” While one side talks about the tools for peace, the back side shows Dad’s first battlefields:

The 399th loaded up on trucks and drove to Baccarat. For most of the men, Baccarat meant a welcome hiatus where the men got dry foxholes, hot food, and their first influx of mail. Lt. Bell, commanding the first platoon, was an educated graduate of West Point and realized immediately another meaning of the name Baccarat--fine crystal. He and his driver T.C. “reconnoitered” in the town and found the factory. There they scrounged—an activity that was less than legal, but a crystal factory in a city getting shelled seemed fair game. When I visited him, T.C. showed me the last beautiful crystal cup from his loot:

I sent this home to my mother and came home from the war and she was drinking coffee out it and I said you want to save that! I sent mother a whole big set of these. This was the last one left when I got home. Baccarat had a big factory there. Bell got some nice stuff. But they started some artillery on that town, and we got out of there right quick.

For the engineers, the plan meant a lot of work. Heavy rain and military traffic had broken down the dirt roads. They were using rubble from the stone buildings smashed by artillery to help stabilize the roads so any kind of vehicle could get through. Even jeeps struggled in the hub-deep mud. In addition, the whole region was heavily mined. Down the east bank they went, clearing mines and fighting through the forests and foothills toward “a huge silent mountain, Tête des Reclos”.3

My sister and I went on a battlefield tour with the 100th Division veterans in 2004. We had gone up a side road to Neufmaisons to have a wonderful lunch of wine, quiche Lorraine, veal, and raspberry tart and were sleepily riding back on the tour bus when suddenly one of the veterans from the 399th, John Day, gave a yell, “Stop! Stop!” He had spotted it from the bus. There, in the rain, looming between the other peaks was an even taller peak. He got out with two other veterans of the 399th first battalion to study it. They all agreed that it was the one—the Head of the Wilderness. It looked intimidating even through a bus window.

Dad’s platoon had a very specific role to play in the conquest of the mountain. They had to build a corduroy road across a swamp at the base of the mountain—in range of artillery and machine gun fire. One dogface in the regiment passed the swamp the day before and described in his memoir how impossible it seemed to get to the foot of the mountain. It wasn’t just wading through the soggy slough that daunted him; it was the prospect of getting essential ammo and food across it too.

All that night, Dad’s platoon worked on the corduroy road. It had meant wading deep in the cold, half frozen muck, cutting down hundreds of birch trees of 6 to 8 inches in diameter and 13 feet long, trimming off all of the side branches to make the logs as uniform as possible, carrying them to the pathway, creating a first layer of crosswise support logs, then a layer of stringer logs laid parallel to the direction of the roadway to stabilize the amount it could sink into the muck, and on top, a roadbed of logs placed as tight as they could be, side by side. Finally, they pounded curb logs staked in place to hold the whole thing together.4 In other words, they had to quietly cut down hundreds of trees, carry them into the deep ice-cold muck, in the darkness of the pitch-black Vosges night, without lights, and with enemy fire coming in. Unlike the infantry, the combat engineer didn’t have the comfort of firing back, and they were always exposed when doing their jobs. Or, as the 325th Combat Engineers morning reports for November 16, 1944, put it, “two squads assisted 1st Bn. under fire and had one casualty from shrapnel. Built corduroy road in the swamps and maintained same.” I think “maintained same” covered a lot of territory because this was a target of the 88s and mortars trying to demolish the resupply route.

The dogface recorded his gratitude and amazement the next day when his unit arrived at the swamp to mount the attack and there was a bridge of birch logs stretching around the base of the mountain. This feat was recognized for its importance in the collage of images from the battle in the history of the 399th:

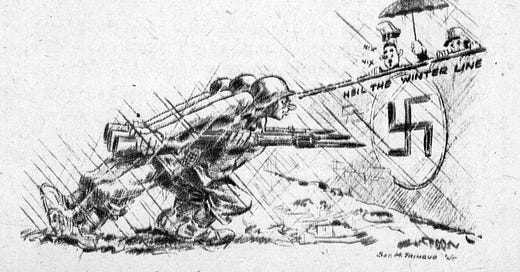

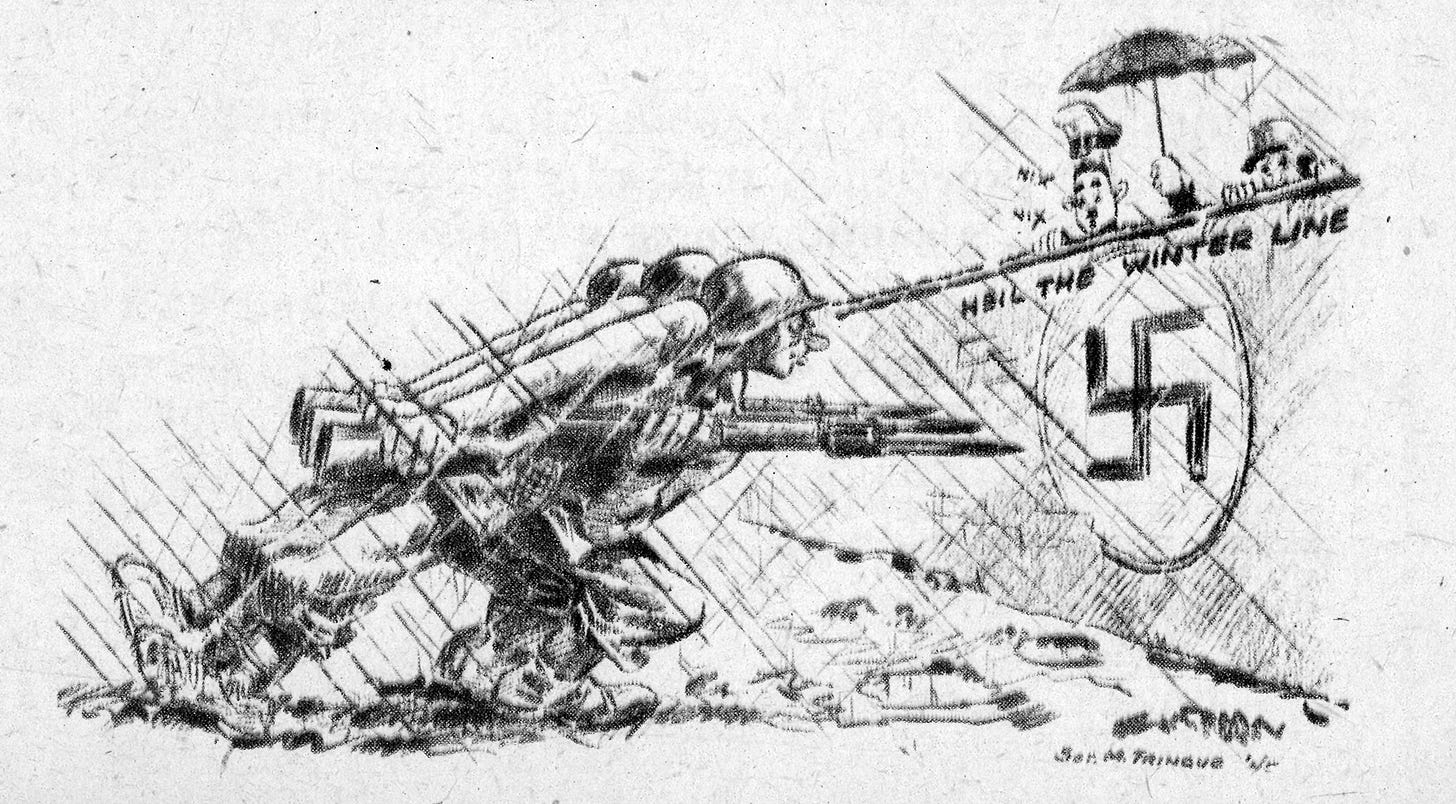

The weather was horrendous. The men “wiped the snow off their weapons with hands that were too numb to load clips into rifles.”5 They couldn’t even undo a button on their pants. The snow was blinding. The sense of where they were easily lost. They came across a tank officer standing in the midst of plummeting mortar rounds, studying his map. As they came up he declared, “well look here. We’re 1,000 yards in front of the 7th Army.”6 The Germans aimed for the red cross on medics’ helmets as they struggled to move the wounded out, when they could even find the wounded in the dark. Once the trail at the base of the mountain was crossed, the men recalled that “the top was nowhere in sight. The hill went straight up into the sky. It was buddy with buddy, squad by squad.”7 In the end they took the mountains but as the 399th history said, “The cream of the 1st Battalion died on that hill.”

One of the themes in my research was the question of who gets to write history and how contingent information can be. For instance, the Army’s records erase Dad’s service as an enlisted man. He was extremely prouder of rising to Sergeant, but the Army has no official knowledge that he was drafted in April 1941. He doesn’t exist before he graduated from Officer Candidate School.

I had known that Dad had gotten a unit citation of some kind. He’d labeled a photo of a ceremony during the Occupation as the day they’d gotten the citation. But nowhere, in any official list of awards and medals or in any kind of general source could I find a reference to the 325th Combat Engineers earning the right to wear a Presidential unit citation. If I hadn’t seen the badge itself sewn on the sleeve of Carl Blanton’s uniform, I would have assumed I misunderstood. Finally, I found a worn-out carbon copy of the citation in Dad's papers. It was an award for the combat team of the 399th, 1st Battalion. Dad’s platoon worked with the 1st Battalion. The citation reads as follows:

The First Battalion, 399th Infantry Regiment, is cited for outstanding performance in combat during the period of 16 November 1944 to 17 November 1944, near Raon l’Étape, France. Overlooking the important Meurthe River city of Raon l’Étape in the thickly forested foothills of the Vosges Mountains, is a hill mass known as Tête des Reclos. This high ground affording perfect enemy observation, barred an assault upon the vital communications city. On the rainy morning of 16 November, the First Battalion launched an attack to clear the enemy from those strongly fortified hill positions. Fighting through the dense pine forest under intense enemy artillery, mortar, machine gun, and automatic weapons fire, the First Battalion, after three hours of effort, drove across the trail circling the base of the hill-mass. A withering, forty-five minute artillery preparation at this point proved ineffective against the deep concrete and log-covered enemy bunkers built into the side of the hills, and it soon became evident that basic infantry assault was the only feasible method for driving the enemy from their positions. In a fierce close-in small arms fire fight, which increased in fury as they climbed the precipitous slopes, the First Battalion wormed their way toward the top of Hill 462.8, key to the enemy’s defenses. Battling against fanatical enemy resistance, they finally reached the crest. Bitter hand to hand fighting developed as the enemy hurled repeated counter attacks against the inspired infantrymen. Once the First Battalion was driven from the hill top but rapidly regrouping they regained their positions. At dark the enemy finally withdrew, leaving the First Battalion in possession of high ground. Throughout, supplies had to be hand carried up the steep slopes under continuous enemy fire. Only the teamwork, coordination, and determination of all elements in this heroic Battalion made the success of this attack possible, opening the gateway through the Vosges Mountains to the Alsatian Plain beyond.

The 399th history pointed out that the citation didn’t even mention hill 538 towering above the others. The 398th fought their way into Raon l’Etape. The 397th captured the route into the pass. I think Dad would have liked knowing that the chief of staff of the German army group wrote in his report after the battle that the 100th Infantry Division was “a crack assault division with daring and flexible leadership.”8

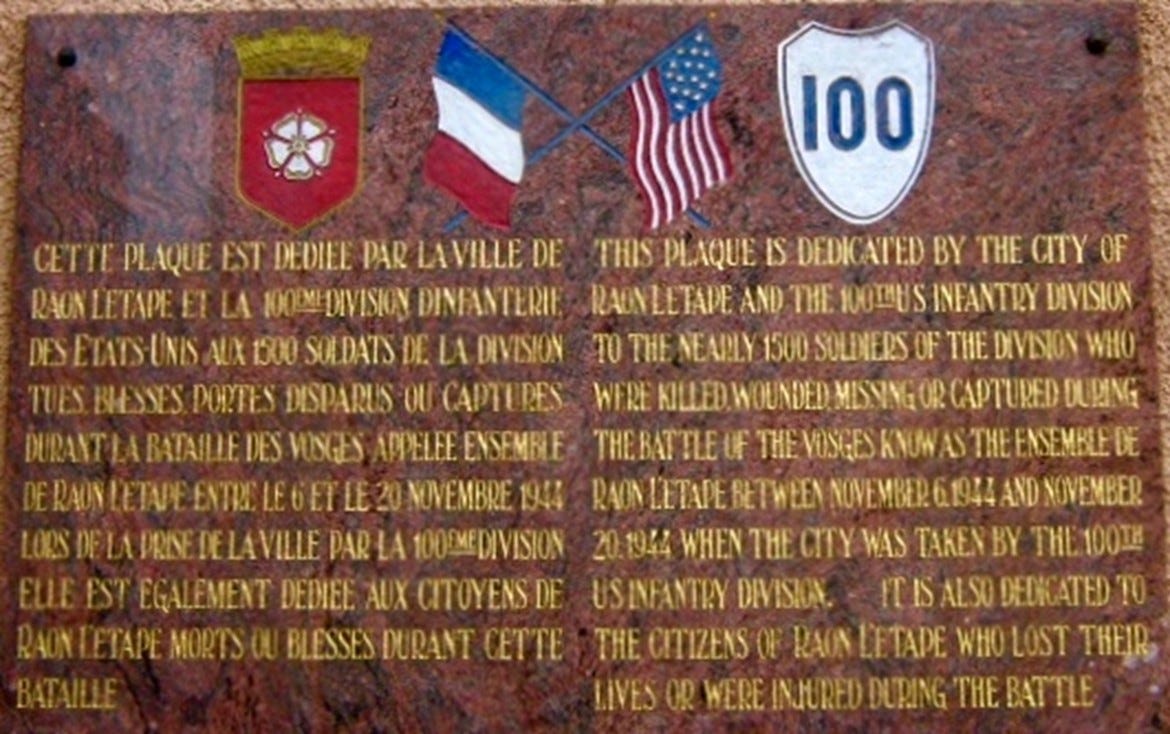

In 2004, on the battlefield tour, we had a ceremony at the town hall where there is a plaque dedicated to the 100th Division and the 1500 men who were killed, wounded, missing, or captured in the battle—and the citizens of the town killed or wounded during the battle.

The scars of the battle were still everywhere in town. One of the men on the tour spotted the building he hid behind at one point and the machine gun bullet scars on the wall that struck while he was there. There was a dramatic statue in the town square, but it wasn’t for World War II. It was a memorial to World War I, the war to end all wars. It hit the men hard who saw it and fought past it. They immortalized it in the Story of the Century.

Clarke and Smith, p. 388.

Clarke and Smith, p. 388.

399th history, p. 33.

Rottman, description of a standard corduroy road.

399th history, p. 33

399th history, p. 41

399th history, p. 41

Bonn, p. 127.

With respect, for the attack on Raon L'Etape, the 398th was assigned to hold the German's attention by firing on the town and environs from across the Meurthe River while the 397th and 399th crossed at Baccarat. Reference the Story of the Century, page 56.

Following the war, the 100th vets would meet annually for national and regional group reunions. This included a solemn memorial service including a set of candles in brass holders. At some point, these were outlawed by the fire marshal. Instead they used hotel water glasses. Realizing the history, it struck me as ironic that those who made the ultimate sacrifice liberating a region known worldwide for its fine crystal should be commemorated using plain glass water tumblers. Working with French military historian Lise Pommois, we were able to secure a set of Alsatian crystal candleholders. One is shown on the homepage of the "Progeny of the Century" Facebook page.