Heilbronn sits in a bowl with a massive escarpment forming an amphitheater around it. The Germans hauled every piece of artillery they could get their hand on to the top of the escarpment, encircling the city and giving clear view of the banks of the Neckar, which the 100th Division had to cross to enter the city. All of the bridges had been blown, the current of the Neckar was racing, the streets of the city were filled with a confusion of rubble impassable to vehicles, and beneath the city was an extensive network of tunnels.1 The 17th SS Panzer Division gathered in a collection of Wehrmacht and Volksturm troops from scattered units who longed to turn and fight and make the Americans pay. There really wasn’t much else they could accomplish in early April 1945.

To the American generals though, who thought there had to be some reason the Germans were not surrendering, it was evidence that Himmler’s propaganda about an Alpine redoubt had to have some substance. It seemed that a battle like Heilbronn was a holding action so the SS and Nazi true believers could reach the redoubt of superguns and underground cities and prolong the war.2 After the intelligence failure before the Battle of the Bulge, no one was willing to discount the idea.3

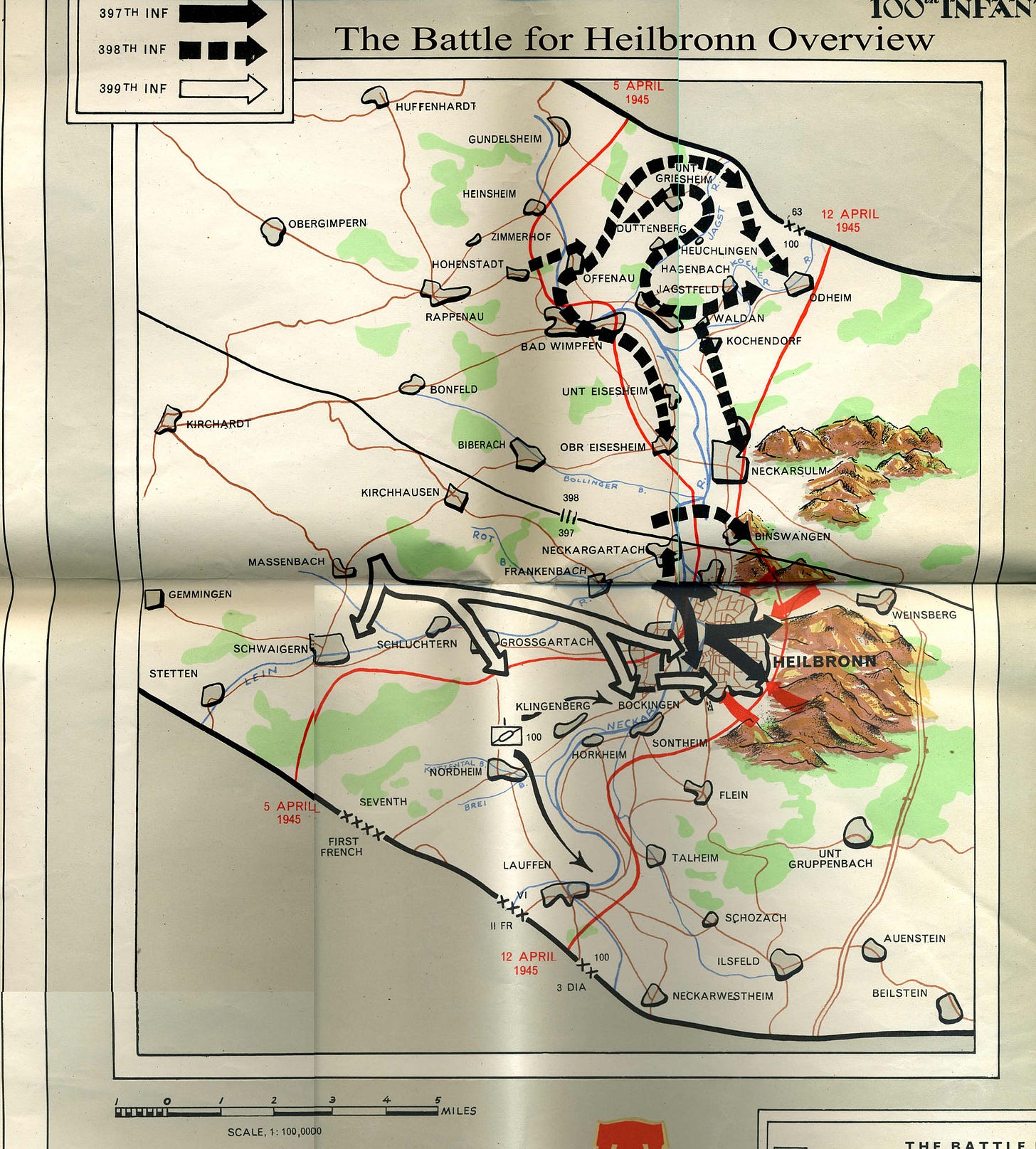

As usual, General Burress, commander of the 100th Division, had studied the situation, saw the problems of a frontal assault, and had a plan. He wanted to form a pincer movement from both north and south to come behind the escarpment. His plan depended on the two units on the 100th Division flanks. The French, who were assigned to be on the 100th Division’s right flank, simply weren’t there. The 398th regimental combat team and the 10th Armored were supposed to be the north flank.

As the historian of the battle said in summary, “The strategy on which it was based displayed Burress’s expertise in river crossing operations and it bespoke his reluctance to sacrifice lives through direct assault when less costly flanking movements had an equal chance of gaining the objective. “4

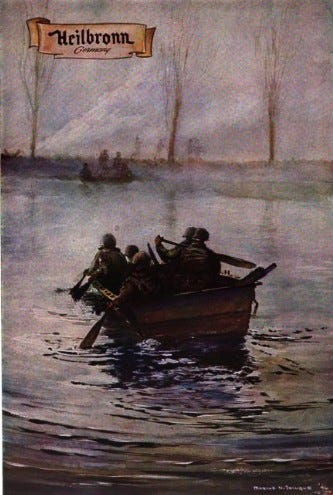

Unfortunately, the 10th Armored, which had wandered off on its own, had gotten into trouble. Brooks, Burress’s superior, ordered him to send a battalion to rescue the 10th on the other side of the Neckar. There was no strategy involved at all. The 10th Armored managed to pull back on its own, stranding the 397th regimental team, and Burress faced what he least wanted, a frontal assault across the Neckar to get to the 397th. The 10th Armored was supposed to have built a bridge north of the city, but when reinforcements rushed to the supposed bridge, it wasn’t there. The engineers attached to the 397th had to get men and materiel across the Neckar using assault boats, small boats that could be rowed across the deep, fast-running river.5 Whenever the boats got most of the way across the artillery on the escarpment opened up.6

For the regular infantry, Heilbronn was a nightmare of hand to hand, doorway to doorway fighting, only to have fresh German troops popping in behind them from the tunnels. As one chronicler said,

War, platoon by platoon, squad by squad, man by man, hit and run, run and hit, factory to factory, house to house, room to room, over dead Krauts, through rubbish, under barbed wire, over fences, in the windows and out the doors, sweating, cussing, firing, throwing grenades, charging into blazing houses, shooting through floors and closet doors—thirty seconds for a puff on a cigarette….Heilbronn was a battle of supply boats, house to house, panzerfaust teams, King Tigers, and the damned little Hitler Jugend. Where in hell are all the bastards coming from?7

To quote the Beachhead News of July 1, 1945, "To all units of the Century and its supporting troops, the Neckar River city of Heilbronn will always mean pure hell. For nine deadly days there--from April 4 to April 12--the fighting teams suffered all combat horrors in the knock-down, drag-out slug fest.”

It was the responsibility of the engineers to get supplies, troops, and armor across the Neckar and bring the wounded back across. The official sequence for a river assault is first manned assault boats, then footbridges across to a toehold on the far side. As the control of the other side expands, then the footbridges are replaced by vehicle-bearing pontoon bridges so tanks, self-propelled artillery, and tank destroyers can cross and provide support. Finally, the existing bridges are repaired or replaced with more permanent structures.8 The vehicle-bearing bridges consisted of pontoons, 12 feet apart, with steel tracks spanning them, held together at each joint by two pins. On the shore, the engineers had to fashion abutments that allowed the vehicles to drop down to water level, cross, and crawl up the far bank. The floats weighed 975 pounds. The steel plates weighed 2,200 pounds. The pins were 4 feet 6 inches long and weighed 65 pounds. When a bay was finished, it was pushed out to the end of the bridge by a boat. A squad manning the “suicide point” would grab it, jockey it into alignment with the previous tracks and pound in the pins with a sledge hammer. Then the pontoon would be anchored against the current with steel cables. A bridge could be built overnight—in about 8 blackout hours. It was no small task, but it was one they had practiced over and over in Tennessee and South Carolina during training.

The problem was the German artillery. One day when we were watching a documentary about the war, Dad reminisced admiringly about the German artillery at Heilbronn. He told me how they had perfected time on target. Down on the river, struggling to get the bridge across, knowing men’s lives depended on them, he would look up and see the muzzle flashes going off all across the escarpment as 88s, screaming meemies, and howitzers fired at different times depending on their individual velocity, timing it perfectly so that all of the shells landed on top of the engineers all at the same time in a great roar, destroying the bridge they were trying to construct. Every night, engineers tried to bridge the Neckar. Every morning, the Germans, allowed them to reach almost to completion. Then they’d unleash the colossal roar as everything would land at their location at the same time.

The author of the 399th Regimental history tried to capture the day:

During the black morning hours of April 8th the 325th Engineers threw a pontoon bridge across the Neckar. At 0800 Sherman tanks and Hellcat TD's thundered across. ...Black crashing 88's saturated the bridgehead area and their roar was magnified in the big hollow factories. Somebody yelled, "here come the Meemies!" and even the Joes in cellars tried to crawl under something. The sky was filled with a metallic shrieking which increased in intensity until the 15 rockets burst like thunder among the factories. The Meemies and 88's punctured the pontoons and the bridge sank. Back to assault boats. … Every morning at 1030 the Meemies would come screaming into the bridgehead and the bridge would go. Two tanks sank in the narrow Neckar. The Engineers rigged up a motor propelled assault ferry which carried infantry and armor into the ever-expanding bridgehead. PFC Leon Januszewdki of the Medics performed numerous deeds of gallantry around the bridgehead for five days when killed by shelling. Smokescreens turned bright day into eerie night.9

Night and day, while working on the bridge, engineers rowed plywood boats across the river, back and forth. Each boat crossing took 7 minutes, long enough to draw artillery.10 While they kept struggling to get the bridge completed, the engineers invented a motorized ferry to keep up the constant pace and get some of the vehicles across. It pulled itself along a rope attached to the opposite bank.11

In 2004, on the battlefield tour, we went up in a newly constructed tower on the west bank of the Neckar to survey the situation. Bob Heller, the medic in Dad’s company, pointed down at the river below and told us that was where they kept trying to complete the bridge. As we were looking down at the spot on the Neckar, one of the men on the tour came over to look where we were pointing.

He was one of the few men who liked to talk—well-honed stories of his daring do. He had been a sergeant in charge of getting supplies to the men of his company. All along the stops of the tour, he would seize the microphone to tell his story about that location. But Heilbronn was unfamiliar territory. He didn’t have a polished story. The tour hadn’t been there before. When he saw where we were pointing, he was struck by a memory. Quietly, he turned to us and said that he had been down there. The engineers had gotten the bridge across but it had already sustained some damage. It wasn’t capable of carrying trucks or tanks, but it could support a man. So he was going to cross with ammunition for the men of his company, but he couldn’t carry it all. One of the engineers volunteered to help him carry the ammo. They crossed over safely, but when they were crossing back from east to west, the artillery arrived, exploding in a roar, flipping the pontoons of the bridge. He made it to shore, but the engineer, nameless to him, didn’t.

He looked at us quietly and said, “there was this officer. He was furious. He grabbed me and demanded to know what had happened to the engineer. When I said I didn’t know, he cursed me out, telling me that it was my duty at all times to know where the men under my command were.” It was clear the memory still had him shaken. My sister and I looked at each other and nodded—it was Dad. Bob Heller, the medic from Dad’s Company C, waited for the other vet to leave then told us that they had found the man eventually. The pontoons had flipped over on top of him in the explosion and held him in the frigid waters of the Neckar, which was a good thing. He was wounded but the cold had kept him from bleeding to death before they found him.

Bob also remembered that on the west side of the bridgehead was an insignia factory, which they had sheltered in. We knew there had been an insignia factory because Dad had put together a little display of some of his. We still have sheets of Nazi insignias: Luftwaffe eagles, Kriegsmarine lapel insignia, bands for SS caps. He had donated quite a bit to a little museum in Whitehall, New York. I still have quite a few. Mom remembered Dad telling her about how he and his sergeant were in the insignia factory, moving around, but the factory had no roof. Suddenly the artillery started to pour in. The gun crews on the escarpment had seen the movement. Dad and Sgt. Manogue ran out of there and into the jeep, sheets of insignias in their hands.

On April 8, they finally managed to construct a bridge that held. By 8 AM Sherman tanks, Hellcat tank destroyers, and two companies of the 399th raced across—though raced meant a speed limit of 10 miles an hour. An artillery officer remembered that they’d stick to the speed limit until they got about halfway across and then they’d gun it in hopes of beating the artillery. Since all the trucks had long ago lost their mufflers, the racket was something.12 With the pontoon bridge holding, they continued to run the motorized ferry. On April 12, six assault boats they were paddling were hit by artillery. Meanwhile in the city, the fighting was still house to house. One of the 399th recalled an odd feeling he had in Heilbronn. He took over a house on April 12, ran up to the second floor to put his machine gun on the table to aim out the window, and felt bad about putting scratches into the beautiful polished table.13

On April 13, the battle was over after 9 days of pointless killing. And on April 13, a GI was crossing a burning lumber yard, when a Sherman tank opened up, and the tanker yelled at him, “President Roosevelt is dead.” The GI was stunned, “I felt as though my own father had died and was bereft with sorrow and abandonment.”14 After all, the calm reassuring presence of Roosevelt had been with them since they were small children.

In the city center, the strains of Chopin’s Polonaise floated through the smoldering town. A soldier had found a grand piano.15

(Longacre p. 227)

(Gimlette p. 272)

(Stafford p. 257)

(Longacre p. 232)

(Longacre p. 234)

(Longacre p. 238)

(Angier P. 72-73)

(Pergrin p. 41)

(399th history)

(Longacre p. 281)

(Knight p. 117)

(Fishpaw p. 172).

(Farris p. 193)

(Farris p. 197)

(Gimlette p. 269)